In awe of first presidential election after fleeing Cuba

by Yariel Valdés González

(Yariel Valdés González, a contributor to the Washington and Los Angeles Blades, was granted asylum in the United States because of the persecution he suffered in Cuba as a journalist. He now lives with his boyfriend in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. The following piece originally appeared in the Blade in October, and it appears here with permission.)

In my 30 years, I have never elected the president of my country, and it is not something I say with pride, but rather with shame. I should have voted for at least three presidential candidates at this point in my life, but that possibility where I come from was exterminated like a deadly pandemic.

There are no presidential elections in Cuba, but rather elected members of the National Assembly who elect the president themselves. This deceptive and convenient electoral system was manufactured several years after the triumph of the 1959 revolution and allowed the same man to govern for 49 years. Fidel Castro fell so in love with power that only a deadly disease could take it from him in 2008.

At that time, he transferred the reins of power to his brother, Raúl Castro, who established five-year presidential terms. The president was allowed to run for re-election, but the same electoral system remained in place. How convenient! At the age of 87 and tired of steering a ship aimlessly for a decade, Castro appointed Miguel Díaz-Canel, a 58-year-old engineer who he previously trained, as a presidential candidate.

My homeland’s president-designate, however, is a carefully stitched marionette puppet who is handled by very thin strings that tell him what to do or say, since it is the Castro dynasty that truly commands the Communist island’s destinies behind the scenes.

Díaz-Canel, therefore, did not have to win the applause of the masses with government proposals. He did not run against opponents for months; nor did he face them in nationally televised debates. Díaz-Canel was elected mechanically and unanimously by 605 National Assembly members locked in a room, not by the more than eight million Cubans registered to vote.

Still, no one can dispute his “leadership.” Cuba does not recognize or legalize the opposition as normally happens in democracies. The brave few who stand up to the regime are persecuted or imprisoned as criminals, accused of receiving money that the United States sends them to “subvert” the “sovereign and democratic order chosen by the people.”

As a journalist in Cuba, I was accused by the dictatorship of being part of “subversive campaigns” that independent media launched against the dictatorship and that, according to them, seek a regime change, when in truth I only wanted to show the world the harsh reality of my people.

I spent 11 months in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement prisons after I asked for asylum in this country. My departure to true freedom, just seven months ago, has coincided with the epilogue of the presidential election in the United States, in which I still do not have the right to participate.

Even so, being a spectator of this process is extremely exciting. Coming from a dictatorship without presidential elections to a country with one of the strongest democracies on earth is a 360-degree turn, one to which I am still assimilating and beginning to understand.

For the moment, my vote, like that of millions of immigrants, was excluded. That did not mean, however, that I could not join the electoral fervor prior to November 3.

It’s a weird feeling, I confess. So many years of inexperience cannot be recovered at once. At times I feel shy, even fearful. It takes some time to get used to the idea that nothing will happen to you for speaking against the president himself.

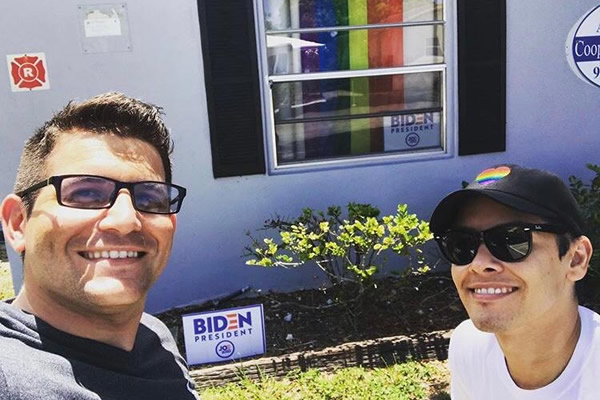

One of my first contributions was to place a banner in support of Biden with my boyfriend in the garden of our apartment. That small poster was, for me, the unequivocal sign of the political freedom that I now have and that for so many years was taken from me.

Then a friend, a fervent pro-Biden activist in Fort Lauderdale, invited me to a rally in support of the former vice president. When I saw myself there I knew that I was really contributing to the good of this nation.

In some way, supporting the candidate who I think is the right one is my way of doing something good for this country, of returning the favor for it welcoming me, of saying thank you: Thank you for allowing me to choose, thank you for protecting me from intolerance, thank you for setting me free, thank you for letting me grow, dream, live.

My contribution to American democracy will definitely not be in statistics, nor will it arrive by mail. My vote is not secret or personal. I throw my vote into the wind every time I go out with a Democratic flag; when I hold up a sign in the name of the blue candidate; when I jump excitedly if someone honks their car horn as a sign of sympathy; when I put my thumb up if a Trump supporter shows me his is down; when I travel the streets in a caravan urging everyone I see to vote.

Because in this country voting can make a difference, especially in Florida, a state that has been key in the last presidential races and where a large immigrant community resides, which grows stronger every day.

Proof of this is the sum of the current electoral contest of more than 23 million naturalized immigrants in the United States who are eligible to vote, according to a report by the Pew Research Center, which represents approximately one in 10 eligible voters in the United States. A new record.

I will not be able to vote in the next election either, but I will be closer. Meanwhile, I will continue to raise my voice for myself and on behalf of the millions excluded. My contribution may not be taken into account now, but definitely no one will be able to silence it anymore.

GUEST COMMENTARY

Volume 22

Issue 9