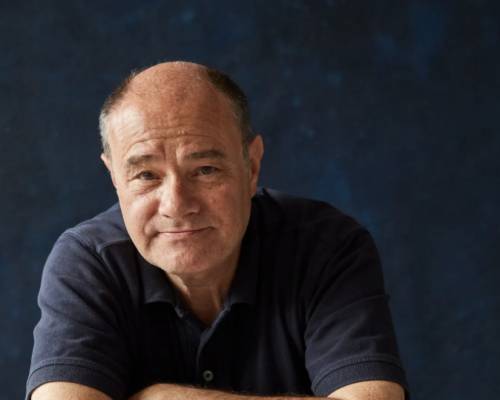

by Mark Segal

(Mark Segal, publisher of Philadelphia Gay News, is the nation’s most-award-winning commentator in LGBT media. His memoir “And Then I Danced, Traveling The Road to LGBT Equality” has been number one on Amazon’s LGBT memoir/biography bestsellers list.)

Just saying that I am humbled is not enough. It is an honor of a lifetime.

By the title of this column, I’m not talking about my age, but something that I’m still processing. There have been many honors over the last few years, but this is something that happens to few Americans, and I never expected it to happen to me. My personal papers of the last 50 years will soon be alongside people like Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, LGBT pioneer Frank Kameny and even Judy Garland’s ruby-red slippers. It seems strange to say, but I’ve been asked by the Smithsonian for my papers and memorabilia, and they are now part of our American history at The Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C.

|

| Mark Segal |

As you read this, my family and some friends will be in the Presidential Reception Suite in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American in Washington, D.C., doing what is called a signing ceremony. That’s when I officially sign over my personal papers and personal memories of the last 50 years, including items from Stonewall, that first Gay Pride March, the Gay Liberation Front, LGBT media, gay youth, senior-housing materials and more. This project has been going on for almost two years now, and my friends at the Smithsonian tell me that they now have 16 square-cubic feet of my life — how strange to put one’s life into square-cubic feet.

During my book tour over the last three years, when I was introduced, many would call me historic, something that seemed to me a little out of place, so when the Smithsonian called, it began a process of me attempting to understand what I had accomplished and the barriers that were placed in the way.

First came the search around the office and home to see what I actually had for the collection. That uncovered pictures, papers and items long-forgotten. Each time the curators at the Smithsonian would smile, and try over and over to explain my place in history, something that I still have trouble contemplating. At one point while I was contemplating this out loud, one of them actually said something like, “You are history and we’re the experts on American history.”

Why the collection was so valuable to LGBT history, I didn’t understand. Most people associate me as a leader in LGBT media and a writer. But that is only a small part of the collection. It also made me realize what the Smithsonian had already understood: While most of my contemporaries had one or two points of our struggle, my involvement in so many of the issues we’ve faced over the last 50 years makes it one of the most complete LGBT history collections. It follows my path from Stonewall to working with Obama’s White House to current battles. And hopefully this collection will give our young leaders the opportunity not only to witness the history, but more importantly, to witness how we took a community that wasn’t a community, built it and struggled to obtain what we have today. A bail receipt from my first arrest in 1970 is a part of the collection, as are three items from the very first Gay Pride March. (We weren’t a parade at that time.)

Writing my memoir, “And Then I Danced: Traveling the Road to LGBT Equality,” gave me a sense of the history I witnessed or created. But when three individuals from the Smithsonian showed up at my front door and explained that America’s history museum wanted my papers, I realized that we fought for pride, for equal rights, for our place in the military and our right to marry the person we love. I am humbled and honored to know the Smithsonian National Museum of American History will preserve and tell our struggle for generations to come.

GUEST COMMENTARY

Volume 20

Issue 2