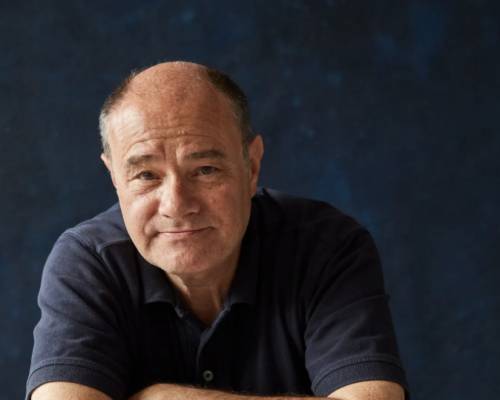

A reporter’s story of lesbians, cancer and loss

by Victoria A. Brownworth

(Victoria A. Brownworth is a Pulitzer Prize-nominated award-winning journalist, based in Philadelphia, whose work has appeared in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Philadelphia Inquirer, The Advocate, Bay Area Reporter and Curve among other publications. The following piece was published in the May 29, 2024, issue of Philadelphia Gay News and appears here with permission.)

This isn’t a story I expected to write for the start of Pride month. This isn’t a story I expected to write again in my lifetime. It is one of the most difficult and emotionally wrenching stories I have had to write in a year of writing difficult and emotionally wrenching stories. Stories about the Israel-Gaza war. About hate crimes. About LGBTQ+ kids committing suicide. About threats of violence against LGBTQ+ people. About erasing LGBTQ people and our words. About the normalization of fascism. About my recently deceased wife.

Last week, ten days after surgery and a series of biopsies, I was diagnosed with cancer. In a particularly eerie coincidence, it was two years to the day that my wife of 23 years, the artist and Drexel design professor Maddy Gold, was diagnosed with cancer.

To talk about my diagnosis, I have to go back. Back to my wife’s diagnosis. Back to the diagnoses of other lesbians. Back to my own previous battle with cancer in my 20s. For decades, cancer has stalked the lesbian community similarly to how AIDS once stalked the gay male community. Yet we never talk about it. I reported a story last week on how lesbian and bisexual women die earlier than heterosexual women. Cancer is a driver of those outcomes.

After I hung up the phone with my surgeon last week, the full weight of my diagnosis — and that I would be facing it alone, without my wife — hit me. I’m still in a state of shock, disbelief and not a little rage that this disease is back to upend my life so soon after my wife’s death.

I also thought about how much lesbian cancer I have reported on over decades. For years, whenever I searched “lesbians and cancer” only my own stories came up. Now at least there’s a special link at the American Cancer Society. ACS states, “The cancers that most often affect women are breast, lung, colorectal, cervical, endometrial, ovarian and skin cancer. Lesbian and bisexual women may be at increased risk for breast, cervical and ovarian cancer compared to heterosexual women.”

The reasons cited include lack of medical care, insurance and money. And fear of discrimination in the health care system. Two partners I had in my 20s — both butch women who had limited incomes as artists and who were uncomfortable with doctors — died of preventable cancers in their 40s. Even my wife had a partner in college who died of metastatic breast cancer. All but one of my closest lesbian friends has had cancer, though fortunately all survived. One friend is battling cancer now. But how is there so much cancer in our community and it’s not a constant topic of conversation and activism?

A few months ago, for Breast Cancer Awareness Month, I wrote about how breast cancer remains a hidden threat to lesbians, bi and queer women. Among the women I interviewed were my friends Mary Groce and Suz Atlas. Mary is a cancer survivor. Suz is still fighting that fight.

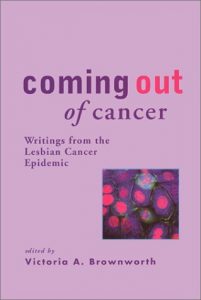

My award-winning book “Coming Out of Cancer: Writings from the Lesbian Cancer Epidemic” was published 29 years ago. Very little has changed in the years since. Outcomes for lesbians and bisexual women continue to be poor — worse for women of color. My mentor Audre Lorde, the first lesbian I knew with cancer, died of it decades ago. One of my closest friends, the artist and photographer Tee A. Corinne, died of cancer, too. So have many of our lesbian icons. Discrimination remains rampant. And we are still dying.

My award-winning book “Coming Out of Cancer: Writings from the Lesbian Cancer Epidemic” was published 29 years ago. Very little has changed in the years since. Outcomes for lesbians and bisexual women continue to be poor — worse for women of color. My mentor Audre Lorde, the first lesbian I knew with cancer, died of it decades ago. One of my closest friends, the artist and photographer Tee A. Corinne, died of cancer, too. So have many of our lesbian icons. Discrimination remains rampant. And we are still dying.

We don’t talk about what happens after the cancer diagnosis. We especially don’t talk about the costs of cancer: physical, psychological, financial. Some people gain weight, some people lose it. In the movies, people with cancer, especially women, look ethereal and beautiful even as they are dying. But in reality, cancer wrecks your looks and your self esteem. My wife was a beautiful woman with strong features and lovely green eyes and thick hair that was black when we were younger and the kind of salt-and-pepper people pay for in salons as she hit her 50s.

Cancer disfigured her terribly. And yet, she remained beautiful to me because I saw her, the love of my life, the woman who fell in love with me in high school and never stopped trying to win my heart. That woman was in this most valiant battle with this violent assailant. And I was bearing witness to the struggle.

I was also fighting the side of cancer we never talk about: the cost. Maddy’s cancer care cost close to a half million dollars in the year she was sick, most of that from the cost of chemo over six months. Chemotherapy is incredibly expensive. Maddy stopped teaching at Drexel a few weeks before she was diagnosed which left all the bills to me, from mortgage to cancer treatment.

What most people don’t realize is you make payments as you go through treatment. And what isn’t covered by insurance can be a lot. Maddy had 24/7 infusion chemo for two of the three days a week of her treatment through a port in her chest and a bag of nuclear medicine attached to it on a timer. That meant when the bag was empty, a nurse had to come to the house, disconnect it, take the nuclear waste away and take Maddy’s vitals.

These nurses were at our house for about 20 minutes to a half hour. It cost $500, unpaid for by insurance for reasons I never understood despite myriad fights with our insurance company. That money wasn’t going to the nurses, either. But it had to be paid: $1,000 a month. There were also the scans and doctor visits and our portion of the chemotherapy. One dose of Keytruda — you’ve seen the ads — when given every three weeks is $11,337.36.

Medical debt, which I have written about for the Inquirer and Alternet, is common and crushing. And you pay for this whether you or your loved one survives or not. A decade before my wife’s cancer, I was bankrupted by my father’s. I will likely never get out from under this debt now.

For lesbians who often do not have family to turn to for help, the costs of cancer on every level can contribute not to survival, but to early death.

I’ve been in a state of barely attenuated grief for a year since Maddy died, struggling with widowhood. Maddy’s cancer was rare, aggressive, stage four, metastatic. What began as a small but persistent cough transmogrified into a grotesque swelling and inflammation in her neck. It took me months of sending her to various specialists and getting her tested for every infectious disease from Lyme to Cat Scratch Fever to Tuberculosis — testing for every disease known to the Western World and some that aren’t — to finally get her a diagnosis in May 2022.

At that point, the oncological otolaryngologist specialist — one of the top in the city that I had used all my journalistic powers to get an emergency appointment with — told us that without immediate intervention, Maddy would be dead within two weeks. Her airway was almost completely occluded by tumors pressing on her windpipe.

We had no time to be shocked. Within hours, Maddy was admitted to Jefferson Hospital and a whirlwind of surgeries, chemotherapy and radiation began. She had two cancers: a thyroid cancer and an esophageal cancer. There was metastatic cancer in her bones: her ribs and back and shoulders. Her thyroid was removed — the source of much of the extreme pain she’d been experiencing for months. She also had to have an immediate tracheostomy to keep her breathing, after which she had difficulty speaking.

This woman who I had known since we were first lovers in high school, a natural raconteur who loved to talk so much that at times during our marriage, I would yell in frustration, “Please just stop talking for five minutes. Just five minutes. Please. For me.” Oh how I regretted those words later. “Be careful what you wish for” has never been such a brutal adage.

After her surgeries, Maddy and I communicated via text and a white board and little scraps of paper. I keep finding those scraps of torn notebook pages with her big scrawling handwriting and unfinished sentences and each time I find another one, it’s a gut-punch. I can hear her voice in those little scraps of paper, some of which are jokes she’s making because she was funny. Oh, was she funny. Maddy made everyone laugh — me, our friends, our families, her students. She was that person who talks to strangers in the market, on public transit, on the street. She made the nurses laugh in the chemo center and her oncologists laugh when we had our weekly meetings with her doctors at the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center.

Among Maddy’s many legacies was laughter and her big infectious laugh. Cancer took so much from her. It could not take her wry sense of humor. It could not take the essence of her.

Even at her sickest, Maddy was still able to make jokes. She sent me an email of her temporary will and at the end of it, she wrote, “Who knows — I could get hit by a bus!” On one of those torn scraps of paper, she wrote simply, “Could have been a Hapsburg!” — a joking reference to her enlarged neck and the notorious protuberant Hapsburg jaw. On still another, “Jim Thompson — so underrated!” (Maddy loved all things noir and was always touting Thompson’s edgy pulp novels of the 1950s and 60s.)

Maddy was brave. She used to tell me all the time that I was the brave one in our relationship, because I did a lot of risky work over the years and rescued animals and sometimes people. And I had a few brushes with death in our years together, including the catastrophic health crisis in August 2016 that paralyzed me.

Maddy’s battle with cancer was hard and she handled it with tremendous courage and not a little grace. I watched her body change in awful ways from the combination of the cancer and the chemo. I watched her learn to care for the misery-inducing tracheostomy and all that entailed. I watched her go through three days of brutal chemo every other week for six months. I watched her lose weight before my eyes and I had to get her on the scale every day so we could keep pumping calories into her as the cancer ate everything.

And then, one night, suddenly, I watched her drop dead in the bed beside me of cardiac arrest, perhaps brought on by one of the drugs in her intense chemo cocktail. It was four days after we’d been told the cancer was getting controlled and a lung aspiration had been clear of cancer. I may never recover from the events of that Friday night and Saturday morning. It was so shocking that one minute she was alive and the next she wasn’t and no amount of CPR or my trying to call her back to me could change that cruel reality.

I held Maddy’s hand for hours after her death. Still so soft. Warm from the warmth of mine, although her hands were always cold — a side effect of the chemo. I had bought her gloves to wear, even in the summer. But at night, when she was in bed next to me, it was just her hand in mine all night. I kept vigil over her to be sure her oxygen levels didn’t drop or the trach didn’t get occluded.

And so I kept vigil over her after her passing.

Every so often, you hear in the news of someone who’s kept the corpse of a loved one — a spouse or a parent or a baby — in their home. I understood it that day as dawn turned to nightfall and I still had not called the funeral home. I didn’t think I could bear to let her go and know she would never ever come back. When her brother would take her to chemo, I always worried I would never see her again. We’d almost never been separated in our near-quarter century together.

How would I go on without her?

When they came to take her away to the funeral home that had handled my grandparents and parents and which was down the street from my grandfather’s photography studio in East Falls, I let them take her in a quilt I’d made for her, because she was always cold. She was still wearing the bracelets I had given her, the amulets to keep her living. They should pass with her into the next world — a piece of me with her.

And then she was gone.

While Maddy was sick, I wasn’t well, but I was so stressed and working so hard. Taking care of her and her treatment was like a second job. I barely slept the year she was sick. And after she died, I was in a state of abject and mordant grief. The loss was brutal and I felt raw and bloodied all the time. The signs of the cancer were there. Before Maddy died. Maybe longer. Nothing registered but her illness. Then nothing registered but her absence and my grief. There is a short poem by W. S. Merwin, “Separation”:

“Your absence has gone through me

Like thread through a needle.

Everything I do is stitched with its color.”

I felt it every minute. The stitch, stitch, stitch of her absence. I wrote about it and her and our life together, memorializing our legacy of lesbian love and fealty.

It’s not the first time I’ve had cancer. I was diagnosed with breast cancer at 26 and again at 28. I had surgery, reconstruction and radiation and I was lucky — I got better. Later, I got sick with other things — multiple sclerosis and COPD from living in other people’s second-hand smoke. Then the paralysis. I navigated all those things. I was always, above all, a survivor, an activist and a fighter.

Now I am in a battle for my very life. I wanted to tell you about that. And about Maddy the cancer warrior, but also the incredible artist and design professor who made everyone laugh and who loved me with her whole heart for decades.

I also wanted you to think about all the women in our community who have cancer now, many of whom may not know it. I wanted to tell you, from the vantage point of a lesbian journalist who has written about cancer since my first diagnosis decades ago, that cancer continues to stalk lesbians and other queer women. I wanted to tell you we are doing nothing about that. And that we must.

SPECIAL REPORT

Volume 26

Issue 5